With increased infusion of computing in our daily lives, computing and computing education fields are pushed to highlight the connections between computing, people, communities, and societies. However, what is under-examined is how teachers make sense of justice within computing classrooms and in other professional contexts that often devalue their expertise and professional wisdom. With more than 15 years of experience working with teachers, we share a case study of a group of high school teachers within the Exploring Computer Science (ECS) teacher community that furthered justice-oriented computing education as co-designers and co-authors of curricular materials and teacher professional development (PD) agendas, and as co-researchers, PD facilitators, and teachers inside and outside classrooms.

Introduction

Computing is everywhere—from mundane shopping to consequential doctor appointments—and is shaping our daily lives in both visible and invisible ways. Complex historical inequities and oppression surface in many different forms within computing that further harm and amplify oppressive forces—from biased datasets to exclusionary tool designs to classrooms where students from historically marginalized groups do not feel they belong. Computing education has recently started engaging with race, gender, and other social markers that interact with computing tools and classrooms. Education efforts have recognized the role of developing critical consciousness among learners and enabling them to "pursue computing as part of and connected to larger struggles for justice and liberation" [16]. However, missing from the narrative is the role of teachers in supporting justice-oriented computing within and beyond classrooms. Accounts of teachers' multifaceted contributions in the design and research processes that resist the normative, peripheral roles ascribed to teachers are few and far between.

Several theoretical frameworks have called for introducing computing as connected to social, cultural, and political realities of people's lives. An example could be to engage learners about biases in computing tools that aid decision-making while learning conditional statements within computer programming classrooms (for example, Ko et al. [12]). Further, design frameworks have argued for designing computing classrooms to be identity-affirming spaces for students to develop disciplinary identities while valuing their complex, intersectional identities as learners (for example, Pinkard et al. [15]). Specifically, pedagogical frameworks have drawn attention to teaching practices as enacted by teachers in classrooms. They have called for "prioritizing asset- or strengths-based approaches that center learners, families, and communities within computing classrooms" [13]. Nevertheless, while some of these frameworks squarely focus on student outcomes, others discuss pedagogical approaches only as an exercise in envisioning better classroom climates. Relegating teachers to a position of receiving pre-designed curricular materials for classrooms not only replicates the hierarchical power relationships between researchers, designers, and teachers, it also keeps teachers from influencing the design of tools such as curricular materials that have implications for their professional practice and their sense of agency and leadership.

Teachers have been involved as co-designers of educational software, curricular materials, and teacher professional development (PD) sessions and, more recently, they have been involved as researchers informing theories around teacher learning within PD spaces.

On the contrary, the few accounts available highlight teachers' roles as partners and designers of educational products to further computing education. For instance, teachers have been involved as co-designers of educational software, curricular materials, and teacher (PD) sessions and, more recently, they have been involved as researchers informing theories around teacher learning within PD spaces. With this article, we present a case study with 12 teachers developed from our work over 15 years with the ECS teacher community to further emphasize and shed light on teachers' contribution to particularly advancing justice-oriented computing education. We showcase the different roles ECS teachers have taken as they co-designed and co-authored curricular units and professional development agendas, facilitated teacher PD sessions and taught the units within their classrooms, and co-researched about teacher learning. We discuss how our case study connects to working in solidarity with teachers and empowering them to see the change we envision in classrooms.

The Why and What of Justice-Oriented Computing Education

Human-designed tools have always reflected aspects of human societies and their multidimensional complexities, starting from cameras that only work well for light-skinned people or medical pulse oximeters that inaccurately measure saturation for dark-skinned patients. As highlighted by scholars who study science, technology, and society (STS), such biases in tool designs emerge as a reflection of societal hierarchies, which shape who designs these tools and participates in the design process, such as testing and informing design decisions [2]. Not surprisingly, similar trends continue to follow throughout computing tool design, where facial-recognition software works most inaccurately for dark-skinned people or how artificial intelligence (AI) tools that learn from historical, biased data reproduce and even amplify discrimination. Examples such as software that allocate housing facilities or help manage insurance claims that aid in decision-making do so while masking the decisions within seemingly neutral algorithms and computational tools [4].

Not only in computing tool design, but historical marginalization has also had implications for computing education in different directions: Who is in computing classrooms, who thinks they can learn computing or want to learn computing, what gets taught as computing, and how does it get taught. One of the most noted research projects within the field of computing education, Stuck in the Shallow End: Education, Race, & Computing highlighted the lack of access to quality computing courses within under-resourced high schools of the country, forcing students from marginalized communities to be "stuck in the shallow end." The authors compared the exclusion to how Black communities were historically kept from swimming pools, creating a notion of "sinkers" [14]. This has since been followed by other studies that have looked at social forces that further keep students from marginalized groups from engaging in computing classes and perpetuate exclusionary practices.

Noticing the inequities within computing classrooms, educational designers and researchers have called for incorporating equitable pedagogies and justice-centered work within computing. Across these frameworks is a call to center students' lived experiences and identity development while making computing learning relevant to their lives (for example, Madkins and Howard [13] and Vakli [16]). Scholars have argued for supporting student identities across different dimensions and at the same time viewing students, families, and communities from an asset framework. Even further, researchers such as Sepher Vakil [16] have called for orienting computing education toward liberatory and justice movements. Overall, there is a call to move away from considering computer science (CS) as disconnected from people, communities, and societies, and instead consider these as connected and intersecting. Along the same vein, pedagogical frameworks have highlighted the role of teachers in realizing these ideas within classrooms and have noted the need for teachers to adopt specific practices that value students and their backgrounds and create spaces for students from diverse backgrounds to thrive within computing classrooms. Only recently, however, have there been efforts that include teachers in design efforts and creating contexts for teachers to contribute to, rather than receive, curricular materials and professional development opportunities. Below, we present a case study of Exploring Computer Science teacher community, and the different roles teachers took on as they led justice-oriented computing efforts within and beyond their classrooms.

Introduction to Computer Science: A Case Study

Launched in 2008, Exploring Computer Science was based on the extensive qualitative research conducted for the book Stuck in the Shallow End: Education, Race, & Computing [14], that highlighted the need for a quality, equity-focused, introductory computing program in under-resourced high school classrooms (https://www.exploringcs.org). To address the gap and enable creation of equitable learning spaces within classrooms, ECS focused on not only providing a year-long teacher-facing curriculum but also a teacher professional development that focuses on computing concepts, equity, and inquiry within computing classrooms [5,7]. The well-researched ECS PD supports teachers through a summer session, four quarterly sessions during the academic year, and another summer session the next year, spanning across two academic years. Interested teachers who successfully complete the PD and teach ECS are recommended for a facilitator development program that further supports them to grow as PD facilitators and facilitate PDs for other teachers nationally and locally within states. The trajectory for teacher professional growth over the years has led to the development of the teacher community around the program, consisting of teachers with a shared vision for equitable computer science education in high school classrooms [6].

In 2022, Joanna Goode and Gail Chapman wanted to revise the program to more tightly connect computing concepts with learners' lived experiences and their cultural backgrounds. They sought to partner with the ECS teacher community to co-redesign the program. Teacher facilitators attending summer 2022 Annual Facilitators' workshop were invited to join as co-designers of the next version of the program. Twelve of the 21 accepted the invitation and joined as co-designers and imagined new lessons and activities and revisions for old lessons and activities within the units for two years (2022–24). During the first year (2022–23), teachers met for eight co-design sessions, a design inspired by the Cultural Competence for Computing (3C) program [17,18], where they explored connections between computing and different social dimensions—such as race, gender, and socioeconomic class—and brainstormed potential opportunities within the curriculum for high school students and teacher PDs for teachers to explore similar connections. During the second year of the co-design effort (2023–24), the teachers co-authored the units, writing, reviewing, and revising lessons and activities jointly and iteratively. Later, during summer 2024, a small group of co-design teachers also joined research efforts in addition to facilitating the first teacher PD for the revised version of the ECS program, locally in their states and nationally for a cohort of eight teachers. And the following academic year (2024–25), most of the co-design teachers taught the revised version of the program. Below we discuss the process and teachers' experiences taking on these different roles and the implications for their upcoming commitments to lead PDs and teach these revised units.

Leading as Co-Designers

The first year of co-design involved eight in-person sessions (~90 minutes each), where the teachers and authors each explored a topic and their relationship with computing teaching and learning (see Figure 1). They brainstormed potential connections and ideas that can be included within the ECS program, either as part of the curriculum or the teacher PD. Each session involved co-designers going through pre-work in the form of short, multimodal materials, such as news articles, videos, and podcasts about the specific topics in addition to preparing a synthesis slide reflecting on the materials. For instance, during the second session on colonialism (see Figure 1), teachers viewed an introductory video on colonialism, read Sareeta Amrute's article on tech colonialism [1], and another article on Native American communities engaging with biased datasets in AI tools [3]. The synchronous sessions (90 min) included multiple rounds of whole- and small-group discussions reflecting on the pre-work and potential ideas for curricular and teacher PD resources. Teachers took notes of their ideas to reference and expand upon while writing and revising lessons and activities, creating a vision for the revision process [8]. For example, in the same session on colonialism, teachers discussed the need to highlight histories and cultural practices within computing classrooms, doing so by making these discussions meaningful for students' lives. For instance, as seen in Figure 2, Flo, a veteran teacher and ECS PD facilitator from the west coast, reflected on how teachers evolved their understanding of integrating computing topics with societal issues. Similarly, her colleague Kristi reflected on the connections between power, one's identities, and therefore their perceptions about other cultures and peoples.

At the end of the first year, an analysis of the teacher interviews (~45 minutes each) highlighted how teachers felt valued and professionally empowered as they participated as co-designers of the ECS curriculum [9]. At the same time, the co-design teachers indicated the significance of doing this work with a teacher community with mutual respect and politicized trust. Teachers were intentional in holding a safe and a brave space for their colleagues to engage equitably as they moderated their participation during discussions in the co-design sessions. They appreciated the opportunities to reflect, share, and listen from educators teaching in diverse political and teaching contexts as they brainstormed new opportunities for classroom engagement.

Leading as Co-Authors

During summer 2023, the co-design teachers moved from being co-designers to co-authors of the envisioned lessons and activities within the ECS program. During this phase, teachers finalized the ideas they brainstormed in the form of classroom lessons and activities. Teachers participated in an in-person session where they started preparing to actualize ideas brainstormed so far and revise the existing curricular units. Most of the preparation involved designing tools required for co-authoring lessons, such as the unit and lesson templates and unit descriptions that shaped the entire revised program by reorienting the lessons and activities within the units. They further developed drafts of two to three new lessons as they prototyped the lesson templates and generated the unit overview charts to coauthor lessons. Throughout, they modeled and practiced the revision process, which involved designing or revising existing lessons and activities, peer review, and reflecting on the feedback they received.

An in-depth qualitative analysis of the audio transcripts and teacher-generated products revealed that teachers demonstrated collective transformative agency as they questioned the purpose (the why) of the different aspects of the curricular program, as well as the entailing pedagogical approach (the how) within the curriculum (see Jayathirtha et al. [10] for more details and examples). Teachers drew from their extensive experience teaching the program, facilitating PDs across different contexts, and their brainstorming from the previous year as they expanded the disciplinary boundaries while revising different parts of the ECS program. For instance, teachers revised the human-computer interaction (HCI) unit description, an introductory text that sets the vision for the unit and shapes the lessons and activities within the unit, to "elevate computers' and computing's connections with social and economic contexts." Teachers revised the description to include sentences such as "students will gain a better understand of the many ways in which computing-enabled innovations impact societies" that later made room for final projects within the unit that support students in examining how computing technologies have differential outcomes for different people and communities, considering both the "positive and negative" ways in which computing interacts with societies. They further revised the teacher PD agendas to reflect the revised program by including extensive experience with Unit 1: Human-Computer Interaction and introducing Unit 2: Problem Solving during the summer session while continuing work on Unit 2 during the first quarterly PD and spreading the other units over the last three quarterly sessions.

An in-depth qualitative analysis of the audio transcripts and teacher-generated products revealed that teachers demonstrated collective transformative agency as they questioned the purpose (the why) of the different aspects of the curricular program, as well as and the entailing pedagogical approach (the how) within the curriculum.

Later, during spring 2025, the teachers further took on the role of revising the curricular units based on a set of external reviews we received for the revised version of the program. Teachers revised the lessons to draw attention to the histories of people's interactions with computing and further supporting teachers to teach the program. This effort has led to deepening opportunities within the curriculum for teachers and students to engage with computing concepts as connected to peoples' histories, communities, and societal issues. For instance, teachers are making opportunities for students to examine who they are, their role in the world as computing students, and their relationship with their communities by maintaining an identity website from the first unit of the program.

Leading as Facilitators

In addition to co-designing and co-authoring the curricular units, teachers have been enabling teacher learning within PDs since last year with the new program. Based on their envisioning of the PD for teachers new to the program, most of the co-design teachers have been facilitating PDs within their states and nationally. The ECS PD starts with the five-day summer session, where teacher facilitators introduce the underlying philosophy of the program through a distinctive teacher-learner-observer approach [7]. Unlike scripted curriculum, the teacher-learner-observer sessions are designed to be an opportunity for teachers to discuss the different ways lessons might be modified for different classroom contexts and learners while keeping the lessons inquiry-driven. They model selected lessons while other participant teachers alternate between engaging as learners and teaching selected lessons, followed by collective reflection that makes instructional practices visible and intentional. At the end, teachers reflect on their experiences and take notes for their classroom teaching. During the academic year, teacher facilitators sustain the learning community through four quarterly PDs, where participants explore subsequent lessons and refine their practice.

What distinguishes these teachers as facilitators is their ability to create brave spaces where educators can examine their own positionality and beliefs about who belongs in computing—a foundation for justice-oriented teaching. They lead discussions with teacher participants around central themes in Stuck in the Shallow End: Education, Race, & Computing. Drawing on authentic classroom experiences, they provide practical strategies for navigating discussions around equity and computing's societal impacts across diverse school contexts, fostering what we term "politicized trust" among participants, a shared commitment to educational justice that acknowledges teaching's inherently political dimensions [6,9].

The facilitation cycle culminates when teachers return the following summer, reflecting on their first-year implementation experiences and connecting with a new cohort of educators. Often, potential future facilitators are identified during this second summer of participation. This regenerative model, where participants become leaders who develop new participants, multiplies the impact of the co-design work and creates sustainable communities of practice committed to justice-oriented computing education. By helping colleagues adapt equity-centered approaches to their specific teaching environments without compromising core values, the ECS facilitators extend their influence beyond individual classrooms to transform the broader landscape of computing education.

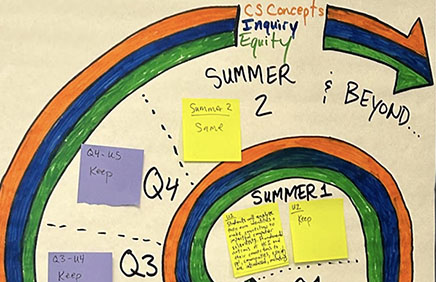

More recently, the co-design teachers, also facilitators, co-authored the teacher PD agenda that accompanied the revised ECS teacher PD and shared the same with other facilitators and reflected on their revision process. They emphasized the need for teachers' ongoing professional and personal growth, relatable professional learning experiences, and opportunities for reflection as teachers become "co-conspirators" for social justice within computing classrooms [11]. As visualized by a group of teachers during this session, the teachers highlighted not only the ongoing and continuous nature of teacher learning but also discussed the model as a way to describe computing teachers' growth—constantly revisiting their own identities and communities as they grow and change their thinking while becoming comfortable with their own positions and relationships. As they designed the PD sessions for teachers to be introduced to the revised version of the program, they resisted language divorced from practice and argued for deepening and clarifying the meaning of equitable teaching practices. They wanted PD to be an opportunity for teachers to ask themselves who their students are and how they can support them to learn computing as related to their own selves and their communities.

Leading as Teachers

Finally, teachers are teaching these lessons in high school classrooms, supporting students in discovering the connections between computing and society. In reflections shared thus far, experienced teachers report productive struggles as they navigate the revised lessons and facilitate new activities. Many are comparing their experiences to their initial experiences teaching ECS, some a decade ago, others five to seven years prior. Unlike previous versions of the program, the revised version requires teachers to facilitate discussions about students' cultural backgrounds, their communities, and connections to computing. For instance, learners are expected to develop an identity website, starting within Unit 1: Human Computer Interaction, and make connections with computing, for instance scratch projects in Unit 3 and data investigations in Unit 4. The teachers found themselves modeling vulnerability and authenticity to create safe and brave spaces where students can form meaningful connections with computing concepts. They describe this as a significant shift in their practice, one that emphasizes reflective teaching while fostering inquiry-based learning within their classrooms.

The leadership within classrooms takes on particular significance given the pervasive influence of computing technologies in society today. Teachers are creating crucial opportunities for students to examine the relationship between computing and identity, community, and social justice at a time when algorithms and AI increasingly shape daily life. In high school classrooms across diverse contexts, these teachers engage youth in learning about consequential topics, such as algorithmic bias, data privacy, and environmental impacts of computing. This helps students develop not just technical skills but also critical perspectives on who benefits from and who is harmed by CS innovations. By intentionally connecting computing concepts to students' lived experiences and community concerns, teachers empower students in their classrooms to see themselves not just as technology consumers but as potential creators who can reshape computing's future toward more equitable outcomes.

Leading as Co-Researchers

Starting fall 2024, when the teachers just completed the first draft of the curriculum, they also joined efforts as co-researchers to better understand and critically reflect on their own work. Teachers participated in a collaborative video analysis session where they co-watched and reflected on their noticings and wonderings from a 40-minute video recording of their in-person session from summer 2024, to uncover what it means to center justice within computing classrooms and to support teachers new to teaching justice-oriented computing within high school classrooms [11]. During the session, teachers examined the structure and content of the PD sessions and designed teacher PD maps to lay out the key ideas. As co-researchers during the co-viewing sessions, they re-watched the video with a transcript and pictures of other teacher-generated products, such as drawings and posters. The video was paused at roughly five-minute marks to take time to complete comments and reflect on observations and thoughts. The co-viewing sessions allowed teachers to engage with their expertise and contribute from their perspectives and experiences from diverse contexts and identities. From analyzing the commented transcripts, the research team concluded teachers called for equitable teaching practices as central to doing justice work within computing classrooms and argued for deepening and clarifying the meaning of equity work—one that centers students' identities and resists the pressure to assimilate students into dominant cultural norms. Further, they highlighted support that new teachers would need further justice in their teaching contexts: continuous opportunities for their ongoing growth, learning experiences tied to their teaching contexts, and opportunities to develop as a reflective practitioner.

Throughout their journey from teachers to facilitators, and then as co-designers, co-authors, and co-researchers, these teachers have demonstrated a progressive development of leadership capacities that extends their influence beyond individual classrooms.

Conclusion

While the role of teachers and their pedagogical practices are illuminated across frameworks that seek further justice-oriented computing education, the ECS teacher community case study presents a closer look at the different roles teachers take as they advocate for transforming computing education and orienting it toward justice. Throughout their journey from teachers to facilitators, and then as co-designers, co-authors, and co-researchers, these teachers have demonstrated a progressive development of leadership capacities that extends their influence beyond individual classrooms. The framework of these interconnected roles offers a model for how teacher expertise can be centered in CS reform efforts rather than relegated to the periphery. This case study, while focusing on 12 co-designer teachers, represents just one facet of the broader ECS community that now includes thousands of teachers and facilitators across the U.S. and Puerto Rico. The expansive network of ECS educators spans diverse geographical and educational contexts and has established a foundation of practice where teachers' voices, experiences, and expertise are valued in curriculum development and professional growth. By putting teachers at the center rather than at the margins, the ECS community shows how education reform can work from the ground up, creating lasting change through shared leadership and collective action.

The ECS teachers have focused on making lessons and activities accessible for diverse teaching contexts while creating opportunities for students to integrate their identities and communities with computing concepts. Their work spans multiple dimensions of justice, addressing social and cultural equity while also engaging with environmental impacts of technology and questions about who benefits from technological innovations. Moving beyond theoretical visions, these teachers have concretely brought these interconnections to life in adaptable lessons and activities, demonstrating how, when supported through structures fostering mutual respect and politicized trust, educators become powerful agents of change. This case study reveals how the abstract goal of justice-oriented computing education becomes realized through intentional design work, collaborative authorship, peer facilitation, and classroom implementation, highlighting teachers' central role in furthering justice-oriented computing education, even if their contributions are sometimes rendered invisible between different frameworks.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to the ECS teacher community, especially the co-designer teachers and facilitators. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant #2417884 awarded to REAL-CS and #2127309 to the Computing Research Association (CRA) for the CI Fellows 2021 Project. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NSF, the CRA, the University of Oregon, or the University of Illinois.

References

1. Amrute, S. Tech colonialism today. Sareeta blog; https://medium.com/datasociety-points/tech-colonialism-today-9633a9cb00ad.

2. Benjamin, R. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. (Cambridge: Polity, 2019).

3. Cipolle, A. How Native Americans are trying to debug A.I.'s biases. The New York Times (Mar. 2022); https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/22/technology/ai-data-indigenous-ivow.html.

4. Eubanks, V. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2018).

5. Goode, J., Chapman, G., and Margolis, J. Beyond curriculum: The exploring computer science program. ACM Inroads 3, 2 (2012), 47–53.

6. Goode, J., Johnson, S.R., and Sundstrom, K. Disrupting colorblind teacher education in computer science. Professional Development in Education 46, 2 (2020), 354–367.

7. Goode, J., Margolis, J., and Chapman, G. Curriculum is not enough: The educational theory and research foundation of the exploring computer science professional development model. In Proceedings of the 45th ACM Technical Symp. Computer Science Education (2014), 493–498.

8. Jayathirtha, G., Chapman, G., and Goode, J. Social media is… sort of our East India Trading Company: High school computing teachers engaging at the intersection of colonialism and computing. In Proceedings of the ACM Conf. on Global Computing Education 1 (2023), 84–90.

9. Jayathirtha, G., Chapman, G., and Goode, J. Holding a safe space with mutual respect and politicized trust: Essentials to co-designing a justice-oriented high school curricular program with teachers. In Proceedings of the 2024 on RESPECT Annual Conf., 215–223.

10. Jayathirtha, G., Chapman, G., and Goode, J. Questioning the why and the how: Collective transformative agency of experienced teachers co-designing a justice-oriented high school introductory computing program. J. Research on Technology in Education 57, 1 (2025), 84–109.

11. Jayathirtha, G. et al. The What and How of Becoming Co-Conspirators of Social Justice in Computing Education: Perspectives from and for High School Computing Teachers (Finland, in press).

12. Ko, A.J. et al. Critically Conscious Computing: Methods for Secondary Education; https://criticallyconsciouscomputing.org.

13. Madkins, T.C. and Howard, N.R. Engaging culturally relevant and responsive pedagogies in computer science classrooms. Computer Science Education: Perspectives on Teaching and Learning in School 101 (2023).

14. Margolis, J. et al. Stuck in the Shallow End, Updated Edition: Education, Race, and Computing. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017).

15. Pinkard, N., Erete, S., Martin, C.K., and McKinney de Royston, M. Digital youth divas: Exploring narrative-driven curriculum to spark middle school girls' interest in computational activities. J. the Learning Sciences, 26, 3 (2017), 477–516.

16. Vakil, S. Ethics, identity, and political vision: Toward a justice-centered approach to equity in computer science education. Harvard Educational Rev. 88, 1 (2018), 26–52.

17. Washington, A.N. When twice as good isn't enough: The case for cultural competence in computing. In Proceedings of the 51st ACM Technical Symp. Computer Science Education (2020), 213–219.

18. Washington, A.N. A change is gonna come: Transforming computing (education) from the margins'. Oxford Intersections: Racism by Context, Meena Dhanda (ed.), (Oxford, online edn., Oxford Academic, Mar. 20, 2025); https://doi.org/10.1093/9780198945246.003.0060.

Authors

Gayithri Jayathirtha

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

College of Education, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

1310 S. 6th St.

Champaign, IL, 61820

[email protected]

Joanna Goode

Department of Education Studies

College of Education

1215 University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon, 97403

[email protected]

Gail Chapman

Exploring Computer Science

College of Education

1215 University of Oregon

Eugene, OR, 97403

[email protected]

Mia S. Shaw

Department of Administration, Leadership, and Technology

School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University

82 Washington Square E. 7th Floor

New York, NY 10003

[email protected]

Figures

Figure 1. The eight co-design sessions during the first year of co-design efforts, 2022–23.

Figure 1. The eight co-design sessions during the first year of co-design efforts, 2022–23.

Figure 2. Example reflection slides from the second co-design session.

Figure 2. Example reflection slides from the second co-design session.

Figure 3. The spiral model developed by the teachers for the revised teacher PD.

Figure 3. The spiral model developed by the teachers for the revised teacher PD.

Figure. Teachers as co-designers, co-authors, and facilitators

Figure. Teachers as co-designers, co-authors, and facilitators

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike International 4.0.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike International 4.0.

The Digital Library is published by the Association for Computing Machinery. Copyright © 2025 ACM, Inc.

Contents available in PDF

PDFView Full Citation and Bibliometrics in the ACM DL.

To comment you must create or log in with your ACM account.

Comments

There are no comments at this time.